Copyright © 2024 My Hemophilia Life.

History

History of Hemophilia

Exploring the Fascinating Hemophilia History: Tracing the Centuries-Old Genetic Disorder's Impact on Our Understanding of Blood Clotting

Hemophilia is a genetic disorder that affects the body’s ability to clot blood properly. It has been around for centuries, but it wasn’t until the 1800s that doctors began to understand what was causing it.

The first recorded case of hemophilia was in the medical literature in 1803, when Dr. John Conrad Otto described a family in Philadelphia with several male members who bled excessively after minor injuries. However, it wasn’t until later in the century that doctors began to realize that this bleeding disorder was inherited and passed down through families.

The term “hemophilia” comes from two Greek words: “haima,” meaning blood, and “philos,” meaning loving or fond of. The credit for coining this term goes to Friedrich Hopff, a German physician who first used it in his medical writings in 1828.

Hopff’s work on hemophilia helped pave the way for further research into the condition. He described it as a hereditary disease that affected mostly males and caused excessive bleeding after injury or surgery.

Over time, other researchers built upon Hopff’s findings and expanded our understanding of hemophilia. They discovered that there were two main types of hemophilia – A and B – each caused by a deficiency in a different clotting factor.

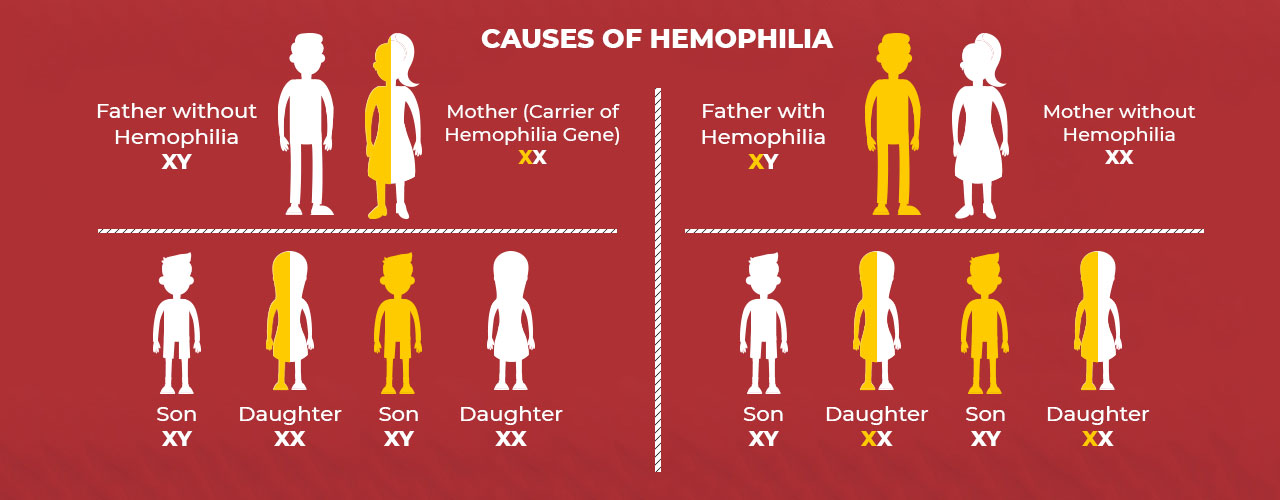

In 1872, Dr. Paul Julius von Ritter identified hemophilia as a sex-linked genetic disorder, meaning it is carried on the X chromosome and primarily affects males. This discovery helped doctors better understand how hemophilia was passed down from generation to generation.

Over time, researchers have made significant strides in understanding hemophilia and developing treatments for those who live with the condition. Today, people with hemophilia can receive regular infusions of clotting factors to help prevent excessive bleeding and manage their symptoms.

Classification

There are two main types of hemophilia: Hemophilia A and Hemophilia B.

- Hemophilia A –

also known as classic hemophilia, is caused by a deficiency in clotting factor VIII. This type of hemophilia is more common than Hemophilia B and affects about 1 in 5,000 males worldwide.

- Hemophilia B –

also known as Christmas disease, is caused by a deficiency in clotting factor IX. This type of hemophilia is less common than Hemophilia A and affects about 1 in 30,000 males worldwide.Both types of hemophilia are inherited from parents who carry the defective gene on their X chromosome. Since females have two X chromosomes, they can be carriers of the gene but usually do not show symptoms themselves.

- Hemophilia C and Hemophilia D –

It’s important to note that there are also rare forms of hemophilia that involve other clotting factors. These include Hemophilia C (factor XI deficiency) and Hemophilia D (factor VII deficiency). Understanding the different types of hemophilia is crucial for proper diagnosis and treatment. With advancements in medical technology and research, individuals with hemophilia can now live longer, healthier lives with appropriate care and management.

Historical background

The first treatment for hemophilia was introduced in the early 1900s and involved transfusing fresh blood from a healthy donor into a person with hemophilia. This method was known as “whole blood transfusion” and was initially successful in stopping bleeding episodes. However, it had its drawbacks – it carried a high risk of transmitting infections such as hepatitis and HIV.

In the 1960s, cryoprecipitate became the preferred treatment for hemophilia. Cryoprecipitate is a concentrated form of certain clotting factors found in human plasma. It is made by freezing and thawing donated plasma and then extracting the clotting factors. This method allowed for more precise dosing of clotting factors and reduced the risk of infection transmission.

In the 1980s, recombinant DNA technology revolutionized hemophilia treatment. Scientists were able to create synthetic versions of clotting factors using genetic engineering techniques.

For many years, there was no effective treatment for hemophilia. Patients with severe hemophilia were often confined to bedrest and faced a high risk of bleeding episodes that could be life-threatening. However, in the early 1900s, researchers began to make significant strides in understanding the disorder and developing treatments. Blood transfusions were also used, but they often caused more harm than good because of the risk of transmitting infections like hepatitis or HIV.

One of the first breakthroughs came in 1937 when a team of scientists discovered that adding fresh plasma (the liquid part of blood) from healthy donors could help patients with hemophilia stop bleeding. This discovery paved the way for the development of factor replacement therapy – a treatment that involves infusing patients with concentrated forms of clotting factors (proteins found in blood that help it clot).

Over time, factor replacement therapy has become more refined and effective. In the 1960s and 70s, researchers developed methods for purifying clotting factors from donated blood plasma, which reduced the risk of infections like HIV and hepatitis B.

Over time, this treatment became more refined and effective. In the 1980s, recombinant DNA technology allowed scientists to produce synthetic versions of clotting factors in a laboratory setting. These new therapies were safer and more reliable than traditional blood-based products.

Today, there are several different types of factor replacement therapies available for people with hemophilia. Some are administered on a regular basis as prophylaxis to prevent bleeding episodes, while others are given as needed when bleeding occurs.

Despite its long history, there is still much to learn about hemophilia and how best to treat it.

The future for hemophilia looks bright and promising. With advancements in medical technology and research, we can expect to see more effective treatments and even potential cures. Gene therapy is a particularly exciting area of development for hemophilia. This approach involves replacing or repairing the faulty gene responsible for causing the condition. While still in its early stages, gene therapy has shown promising results in clinical trials, with some patients achieving sustained remission from bleeding episodes.

In addition to gene therapy, there are also several new drugs being developed that target specific aspects of the blood clotting process. These medications have the potential to provide better control over bleeding and reduce the need for frequent infusions of clotting factor. Beyond medical treatments, there is also a growing focus on improving quality of life for individuals with hemophilia. This includes efforts to increase access to care, improve education and awareness about the condition, and support research into non-medical interventions such as physical therapy and psychological counseling.

Overall, while there is still much work to be done, the future looks bright for those living with hemophilia. With continued investment in research and treatment development, we can hope for a world where this condition no longer poses a significant burden on those affected by it.

Causes

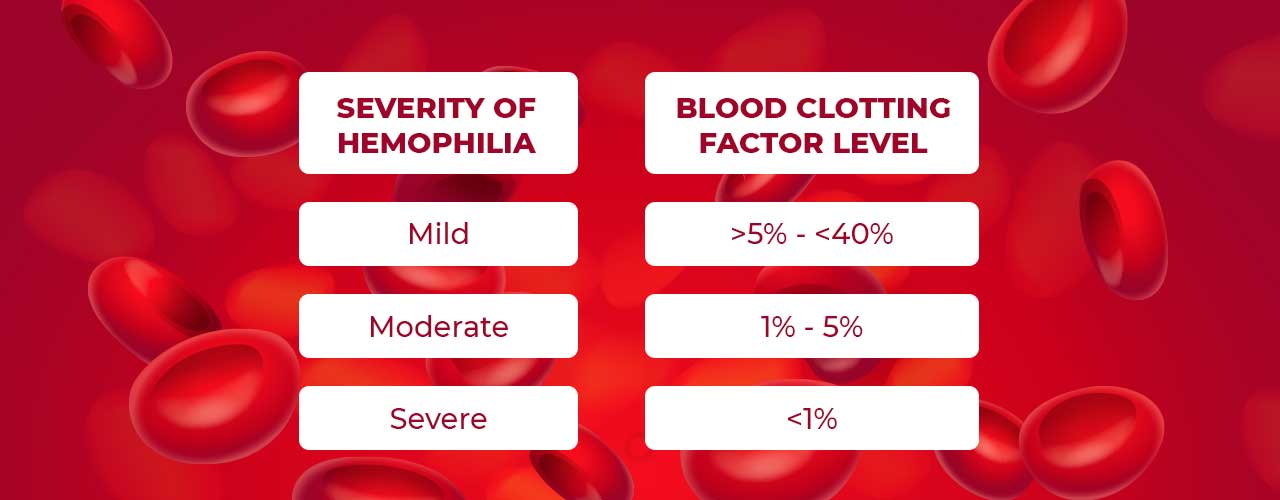

The coagulation cascade is a process in our body that stops bleeding where blood platelets coagulate together at the site of the wound to form a clot. Then a more permanent plug in the wound is created by the body’s clotting factors. A low level of these clotting factors causes Hemophilia.

- Genetic Inheritance – Hemophilia is inherited genetically, it is caused by a defect in the gene that is responsible to determine how the body makes factors VIII, IX, or XI. As these genes are located on the X chromosome, it makes hemophilia an X-linked recessive disease.

- With no family history – Some studies showed that there was no known family history of the condition. There are some cases where the boy is born with hemophilia without any Family history of the condition. Such cases may occur due to a gene change developed spontaneously in the boy’s mother, grandmother, or great-grandmother.